Recently I finished reading Make it Stick, which is probably one of the best books on learning ever written. In the book, one of the topics that the authors discuss are illusions of knowing and they even dedicate an entire chapter towards explaining how to avoid these illusions. Understanding what are these illusions and how to avoid them is critical to any learner and in this article, I will explore exactly that.

The illusion of knowing is the belief that you have understood and learned something, when in fact you haven’t.1, 2 A good example of this is a student reading through a textbook several times and declaring that she has learned the material. However, if you asked this student the explain the main concepts discussed in the textbook and see whether she can apply them in practice – you will probably see that the student has a superficial level of understanding at most.

I know this because I have been that student many times and have met such students myself – when I was studying economics there was this guy who always 2 days before the exam would read through the entire 300-page textbook (full of complicated economic concepts) – then he would go into the exam, would barely get a pass and then wonder why he got such a bad grade.

The truth of the matter is that just reading and re-reading the material is not sufficient to learn it. In fact, studies1, 3 have shown that re-reading is an ineffective study strategy. However, many learners do it nevertheless, because it is easy and it creates this false feeling of mastery – the illusion of knowing.

The illusions of knowing are not limited just to when one is reading the material – they arise in all kinds of situations, for example, on a daily basis we make judgments on various topics such as should we raise taxes, should we ban GMOs, should we invest more money into renewables, etc. thinking that we have a pretty good understanding of the topic – when in fact, we know very little and if somebody asked us to explain the topic in depth (e.g. what are GMOs and how they work) we would not be able to do it.

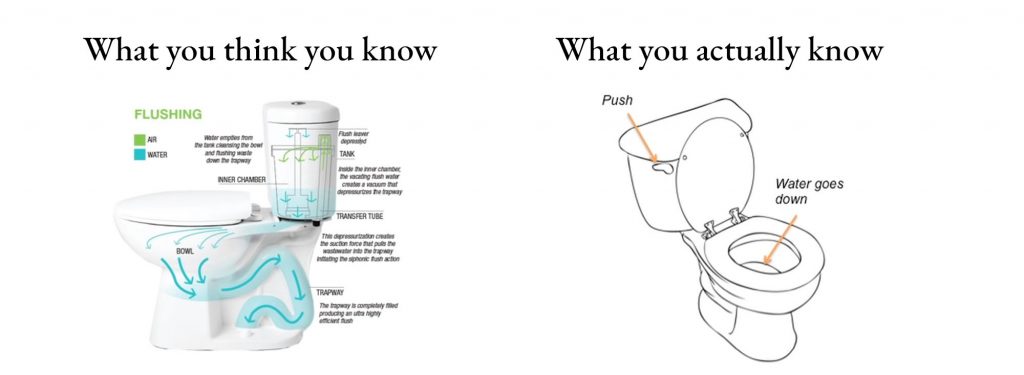

There is a fascinating Ted talk by Philip Fernbach in which he discusses several studies that investigated whether people’s perception of their understanding of a subject is actually accurate. It turns out that people are overconfident in their knowledge. For example, most people tend to overrate how well they understand things like how a toilet works or how a bicycle works.4,5 You might think I understand how a bicycle works, but if I asked you to draw me a drawing of a bicycle – the average person would draw something like in the picture below.

As you may have inferred from the examples above, we are quite bad at judging our own knowledge and we tend to overestimate what we know especially when we know very little. In fact, this tendency of people overestimating their knowledge, when they know very little about a certain topic, has been documented in several studies1 and is known as the Dunning Kruger Effect, which states that “people with low ability at a task overestimate their own ability, and that people with high ability at a task underestimate their own ability”. So the real problem is not that we do not know, the problem is that we are often are not aware that we do know not.

Why are we such poor judges of our own knowledge?

The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.

Socrates

The authors Make it Stick provide two key reasons for our poor judgment. Firstly, as illustrated by the Dunning Kruger Effect, we are often just not aware that we have fallen prey to the illusion of knowledge. Secondly, there are a lot of ways of how we can be led astray – we are susceptible to a slew of cognitive biases and techniques that can distort our perception and understanding.1

I am not going to discuss all of these biases and ways in which our understanding can be distorted in-depth since this is a really huge topic (a bunch of books was written about it e.g. Thinking Fast and Slow). However, here is a brief list of various documented human tendencies in which we deceive ourselves:

- We tend to selevtivelly look for evidence that confirms our beliefs or values (while ignoring contrary information) – confirmation bias

- We tend to think that we knew something was going to happen after the event has already happened, or in other words we have tendancy to perceive past evenets as having been more predictable then they actually werer – hindsight bias

- We tend to believe that we understand complex phenomena quite well and deeply, when in in reality we have a superficial understanding at best – illusion of explanatory depth

- Our memories are influenced by our social circle, and if several people report that something has happened slightly differently from the way you remember it has happened, then these other memories by other people will be incorporated into your memory (although they might be false) – memory conformity

- We tend to believe that other people share our beliefs, while that might not be true – false concensus effect

- Our decisions tend to be influenced by a particular reference point aka an anchor – anchoring

- We tend to ascribe success to ourselves, while failure to external factors – self-serving bias

- We tend to rely on things or examples that are easy to recall on the spot when making a decsion, if a memory is more difficult to recall we often deem it less important – availbility heruistic

- If sombody asks you to imagine a ficticious event vividily you might begin believing that this event has actually happened – imagination infilation

- Often if we do not stop to think and go with our intuition we are susceptable to various biases and can make mistakes (of course, this is not always the case, intuition can often be useful) – this is known as system 1 thinking and incorporates a lot of the aformetioned biases

- etc.

How to avoid illusions of knowing?

So we have established that we tend to succumb to illusions of knowledge and that this can be extremely detrimental for people who want to learn something – since we might believe that we learned something, while in reality, we didn’t. This can be a serious obstacle when trying to learn effectively. So what is the antidote to this?

“The truth is that we are all hardwired to make errors in judgment. Good judgment is a skill one must acquire, becoming an astute observer of one’s own thinking and performance. “

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel – Make it stick

Well, the first step towards making ourselves immune to illusions of knowing – is being aware that we are susceptible to them. So congrats if you have reached this point in this article you have already made one step towards avoiding the illusions of knowing. The second step, and the best way of knowing whether you know something is actually testing your knowledge. So if you believe you understand how the toilet works – take out a pen and a sheet of paper and write down an explanation of how the toilet works (without looking at any sources or checking the toilet in your house 😉) – also draw a schematic of the toilet with different parts etc. Then if you want to take it a step further, take this schematic that you made to a toilet expert (i guess a plumber) and ask her to evaluate it. If she says that it is accurate – congrats you understand how a toilet works 🎉

Of course, there are many different ways to test your knowledge. However, it is important to keep in mind that not all tests are equal. The first tendency that we might have is to test ourselves superficially (so basically no exercise, you just try to test yourself in your head) and lookup an answer and conclude that we knew it all along (a great example of hindsight bias). So if you really want to make sure that you know something you need to test it thoroughly – try to explain it verbally, try to write down the explanation, try to retrieve the information from your memory, and if you can, try to get your understanding validated by other people, by your peers or even better by experts in the relevant field.

Of course, depending on what you are learning the tests might differ – for example, if you want to test your language knowledge it might make sense to try speaking with someone in that language or taking an official language test. If you want to test your coding skills – it might make sense to build a real app, etc. You probably get the point – the more realistic and thorough the test is, the better indication it will provide on how much you actually know.

Another great by-product of testing yourself is that this is actually one of the best ways of learning something, according to the authors of Make it sitck1. So even if you will fail your test you will get 2 valuable things out of it – firstly, you will know that you do know (which is great since this means you have avoided the illusion of knowing); secondly, you will learn something new and deepen your knowledge in the field.

References

- Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make It Stick. The Science of Successful Learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Glenberg, A. M., Wilkinson, A. C., & Epstein, W. (1982). The illusion of knowing: Failure in the self-assessment of comprehension. Memory & Cognition, 10(6), 597-602.

- Weinstein, Y., Sumeracki, M., & Caviglioli, O. (2018). Understanding how we learn: A visual guide. Routledge.

- Lawson, R. (2006). The science of cycology: Failures to understand how everyday objects work. Memory & cognition, 34(8), 1667-1675.

- Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. (2002). The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive science, 26(5), 521-562.